The Network: Digitising classrooms around the world

This is a repost of an original article published in No 8 issue of CoFounder in early 2017.

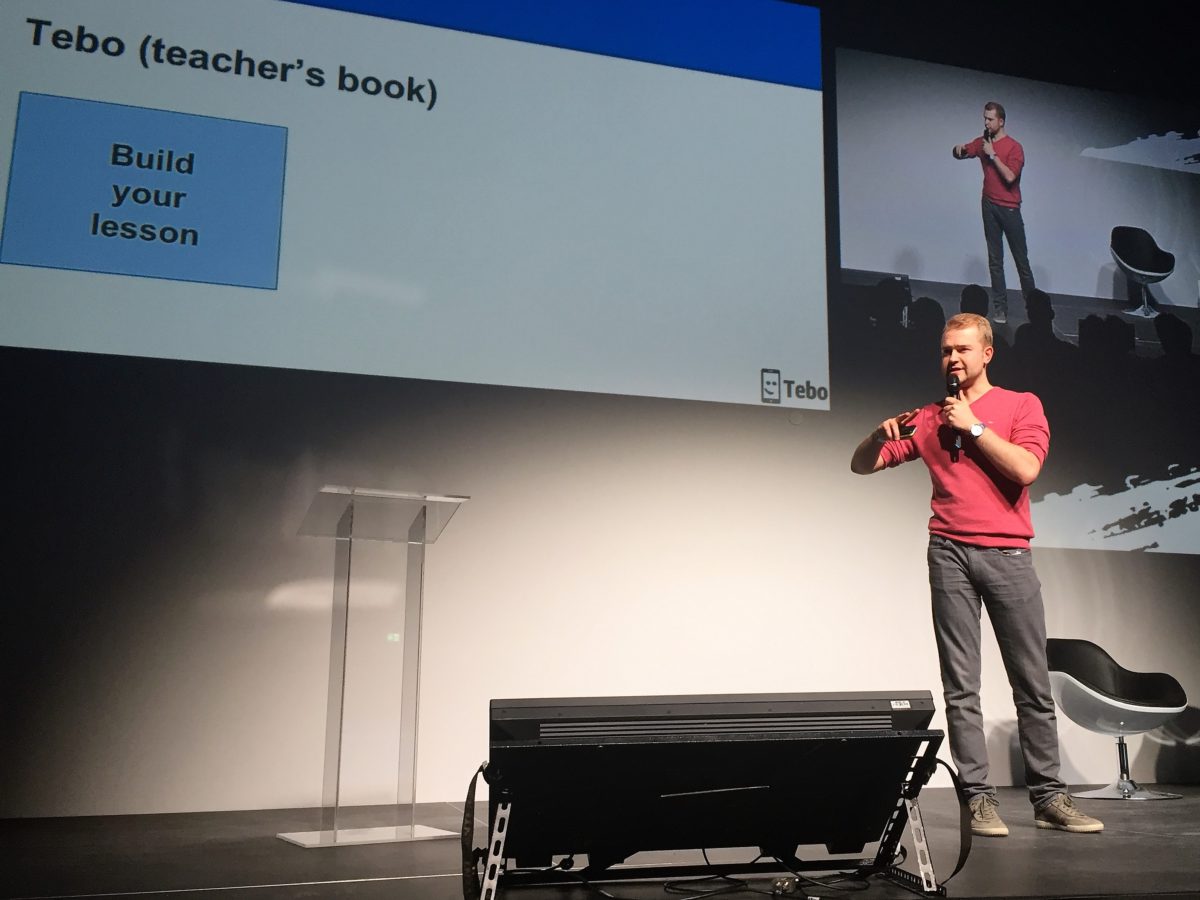

Entrepreneur Tõnis Kusmin is planning to revolutionise schooling around the world.

Tebo initially launched a few years ago in Estonia as an NGO called Silmaring – building an offering in the education sector which included many products, including learning videos. “I founded the NGO because I wanted to change education with technology. So we were doing many things”, Kusmin, 31, describes the early days of Tebo. “The idea of a marketplace for education is a spinoff from the NGO.”

To take the platform to the market and raise investor capital to do that, Kusmin and three others created Tebo in November 2015. In just over a year the company has built the team, the product in 3 languages, signed up one third of Estonian teachers, attended the Startup Chile accelerator, got their first paying customers and raised seed investment. “We have got investors thinking with us. With their knowledge, I have been able to develop this way faster than we would have otherwise”, says Kusmin.

In the last three months, Tebo has started making sales and the number of paying schools has increased from 3 to 30.

Tebo is a content exchange for teachers – a kind of online teacher’s book – aiming to put everything teachers need to run increasingly digital lessons into one place. It stands out among many other platforms – which allow sharing of slides or PDF files – with tools to create interactive exercises. “The future of education does not happen on paper anymore, it happens on smart devices”, Kusmin says. “We are giving teachers tools to build interactive exercises and share these exercises so that they can engage their students with tablets or smart devices in the classroom – not only show them the slides.”

“Today, the majority of education still happens with lectures and textbooks, which is boring for students and extremely ineffective”, he says. By the mid-20th century, science had already proved the need to involve students with interactive lessons, but the technology has been lacking mass adoption.

“Now, when smart devices are cheap enough and schools are using them in the classrooms, teachers are starting to turn away from PDFs and slides”, Kusmin says. “It has been impossible for a teacher to engage the whole class at the same time, unless she is a superstar, but most of the teachers just cannot handle 1-on-1 discussions with 30 people simultaneously.”

The platform focuses on content sharing between teachers and for teachers – exercises, learning videos, games. It lets teachers create learning games in 15 minutes.

Students can open them in class with any Internet-connected device and can quickly fill in exercises under the teacher’s guiding eye.

That should solve the problem of students’ different speeds in the classroom. “We are building a dashboard where you, as a teacher, can see online in real time how your students are doing. So you know that Mary and Carl need some help right now, they have been stuck on the same exercise for 15 minutes, but the rest of the class is doing fine, or you might see that five students have already finished their exercises and you can give them something to develop them further”, Kusmin describes.

One would expect that taking the tool into every classroom in the world is quite a challenge, but it’s not too worrying for Kusmin. “It is not a hard thing to do. It is rather simple”, says Kusmin. This sounds a bit optimistic, but he has an explanation. “Teachers are looking online for tools like that all the time. Moreover, teachers are highly networked; they chat in coffee rooms, schools, they attend seminars and events.”

Tebo’s take-up rate in Estonia is stunning, at 33% of all teachers, but in other markets it faces the same problem that social networks have when they launch – when you were the first person on Facebook, there wasn’t much point in you being there. The social network has to have a scale for it to have a point.

Tebo mitigates the first-joiners dilemma with the toolset or software it offers, on top of the content exchange platform. “If you are the first teacher signing up from a new country, then you would have the same value from the software as you would if you were the millionth teacher signing up, but it makes the difference in the network. At first, the library is empty. When you are the hundredth or thousandth teacher you might get something out of it, but once you are the ten-thousandth teacher it is amazingly good – that is why we focus on the country and build up the network”, Kusmin says.

That also includes translating the platform. “It is rather important in education”, Kusmin says, but added that, thankfully, early-adopters are not so much hampered by the language than the masses. “Teachers who use the tool are early adopters, and they speak rather good English.” To the big markets, like the United States, Tebo is going in with a natural sciences spearhead, focusing its marketing on physics, chemistry, biology and geography.

Most of the functions are free – you can upload content to share with others for free – but for downloading there are limits on the free plans. So a teacher can either buy a 9 euros per month premium account for all they can use packages, or schools can buy licences for their teachers.

Tebo is tapping into schools’ budgets for learning content – something that today mostly goes into printed content. “Digital is growing rapidly, but that money also goes to publishers. At the same time, teachers are creating new content every day and some of it is really good, maybe not all of it, but some is. If other teachers use their content they should get revenue from it”, Kusmin says.

“We are sharing part of the revenue back to the teachers; we made the first payments in Estonia in January. Teachers got real money in their bank account for uploading the material they have on their hard drive anyway”, he explains.

In larger countries, a successful teacher could well earn a second salary from the content – in a small market like Estonia, it is more likely to be like a 13th month’s salary for the year. “If it’s sitting on your hard drive anyway, why don’t you make 200 euros a month for uploading it”, Kusmin says.

To hear more from the co-founders and their stories, subscribe to CoFounder Magazine.