Russian robots will take your job. Really?

“In the simple tasks, everyone will be replaced by robots in the near future.”

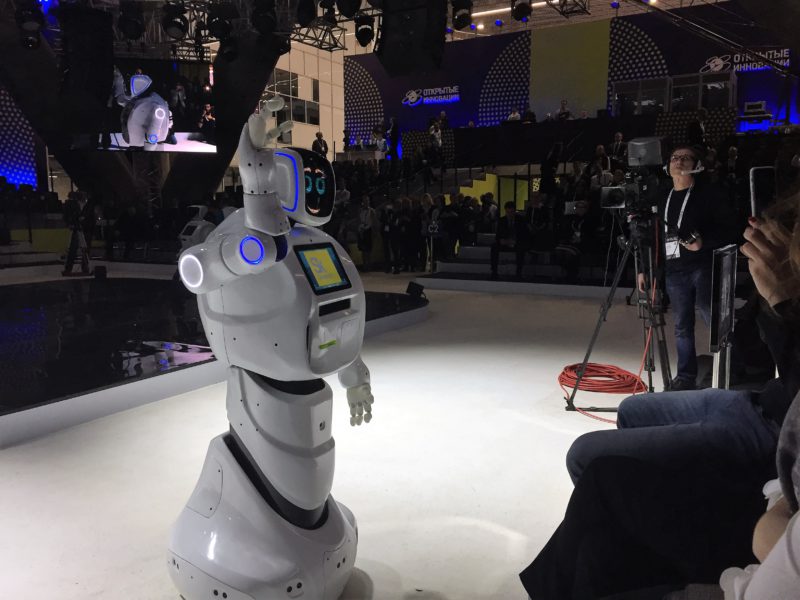

THE SMALL ROBOT ROLLS ACROSS THE STAGE TOWARDS THE AUDIENCE AND GIVES A HIGH-FIVE. FOLLOWED BY PHOTOGRAPHERS CRASHING INTO ONE ANOTHER TO GET THE BEST SHOT.

Promobot’s launch of a new version of its marketing robot in October, on a big stage in Moscow, was a product launch that many Silicon Valley companies would be proud of. Chief Executive, Alexey Yuzhakov, is jumping up and down on the stage, in sync with rock music tunes in the background, while sound- and light-technicians do their utmost to use one of the best-equipped halls in the country. The journalists are lining up for interviews.

And it’s not all just robotics hype – the product must be one of the top marketing robots one can buy for money anywhere in the world. How did they come to this?

The story of Promobot started in 2013 in Perm – hometown to all its founders. Anyone outside Russia might remember the town for some tragic plane crashes or nightclub fires, but they know very little of the town which is 1,400 kilometres, or a 21-hour train ride, east of Moscow. In the middle of Russia, Perm is almost on the eastern border of Europe. It was a closed city for 50 years, making aircrafts and spaceships, and it boasts being home to some of the top technical innovations of the Soviet Union.

Perm delights its visitors and inhabitants with winter temperatures that can drop below -40 degrees Celsius any time from December to February. The harsh winters, which force you to stay inside and focus on mental work, make it very similar to the tech hubs in the Nordic countries.

Three engineering students, among those Oleg Kivokurtsov, who I meet, started to get deep into robotics during their studies at the Perm National Research Technical University – one of the best technical universities in Russia.

Yuzhakov, a successful smart home entrepreneur at the time, came to visit the university, his alma mater, in late 2013. Oleg walked over to him, offering to build robots for smart homes, after Alexey’s lecture on innovation.

Nothing concrete happened at the first meeting, but by the next time they met Alexey already had a plan in mind.

“Guys, I have an interesting idea”, Yuzhakov started. He explained to the team the first idea of Promobot – a childsized autonomous robot, whose main use would be for marketing. The robots are designed to serve customers, highlight products, offer critical information to customers, provide help with navigation and broadcast promotional information for companies.

“I understood that direction would be very prospective”, Kivokurtsev told CoFounder in an interview. The three engineering students and Yuzhakov teamed up to build marketing robots – the students put in the work and the entrepreneur put in the initial capital.

In just four months the first prototype was ready. Yuzhakov introduced the early Promobot to his contacts in the construction industry – to cinemas and business centres.

“Those companies said yes, we would like to buy it. Our price for one robot was 10,000 dollars. We sold it, and after three months gave them this robot. After that, we built more and more and in 2014 we sold 20 robots”, Kivokurtsev said. “We built new mechanics because we understood that interest in mechanics attracts more attention, attracts more customers, attracts more traffic and it can also increase business options.”

Since then the startup has had to just keep up with growth. In 2015, the Moscow Technology Institute bought 50 robots, one for each of its 50 departments all around Russia. Then Forbes Magazine covered the weird little robots and sales exploded. “After that, we uploaded all of our manufacturing to nine months. We sold 100 robots from only one story”, Kivokurtsev said.

In addition to Russia, there are Promobots in action in China, Kazakhstan, the United States, Ireland and the United Kingdom, working in the airports, cinemas, business centres and shopping malls.

The reach is global, but the production premises are so far not massive – with 25 staff working in 500 square meters, building a robot a day. “If we need to build more, we can increase our manufacturing. We are building by ourselves, all the mechanics, all the plastics. We are uploading software, writing software and we are buying the electronics in China. We are developing some types of programs by ourselves, some of them we find open source, some of them we buy”, Kivokurtsev said.

The Promise

Ideally, the robot could be the first point of contact when you enter a store or bank, directing you to the right people or desk. You can ask it any question and they try to help you – so it all comes down to software and interaction with the robot. “Our robot can recognise speech in places with lots of noise. It will understand everything that people are saying. It’s really important for the robot, because in human and robot interaction, speech is central”, Kivokurtsev explained.

As the employment market in the western world continues to be lacklustre, and availability of people for simple tasks tends to be limited, the opportunities are limitless – the firm is already building different versions of the product for banks, airports and shopping malls, with hardware and software differing based on the final usage.

“The market has a big problem with employment. We hire the administrator, hire the promoter, hire everything. It’s difficult. We need a break and we should solve that problem. In the simple tasks, everyone will be replaced by robots in the near future”, Kivokurtsev said.

In addition to general robotics fears, surely there are some cultural challenges for mass adoption. One has to admit that talking to a robot, which is roughly 1-metre tall, is a strange experience – especially when there are grownups standing next to the robot at a trade fair. In addition to the user-side challenge, stores are also not that used to the new gadget, which does need to be charged and maintained. Visiting a

In addition to the user-side challenge, stores are also not that used to the new gadget, which does need to be charged and maintained. Visiting a tele-operator store in downtown Moscow I see Promobot in the corner, switched off for a while. “It’s not working”, the customer service lady tells me briefly. At Slush, too, a competitor of Promobot stands sadly, with its head down, at the stand of a Finnish telecom operator. Even for a massive trade show, where a cool gadget would attract hundreds of visitors, the company who dragged it to the venue has not ensured it would work. At the trade shows I have seen Promobots, they have been in use, but Kivokurtsev admitted that maintenance and teaching clients is a process of its own.

“When people buy it, they can do anything that they want with it. If they decide that they don’t want to use it, they can do so”, he said. “If your sale’s proposal is that we’re doing an interactive thing where people can go and talk to it and it replies, and if the store just has it in the corner, it would be a beautiful little thing.

“We have special people who will talk to customers every week and say, ‘Hi, how are you? Are you using it? How? Have you got some problems? Can we help you?’ We organised that service in November and I think that will solve the problem.”

“The company has service partners on different continents who can get to the robots in use and fix mechanical problems. In our robots the mechanics are simple. We understand that if it is simple, it will be easier to maintain”, Kivokurtsev said. “We can fix the software ourselves if the robot is connected to internet – our programmer can fix everything.” In late 2016, Promobot raised 150 million roubles from the government fund

In late 2016, Promobot raised 150 million roubles from the government fund IIDF, the biggest investment in robotics in Russia. This is pennies when compared to Promobot’s closest competitor Aldebaran, now Softbank Robotics, which has raised 1 billion dollars. With the help of a global media push, the firm has sold some 10,000 humanoid robots, which are aimed at helping people in their everyday lives. Kivokurtsev is not certain there is much demand for this any time soon though: “They made a big, big mistake. They started building robots for consumers. People say why I don’t need robot? I have a cell phone. I can use any app. I can turn on my lights on or something [with that].”

Since then, the rival has positioned itself more directly against Promobot. “It is a small robot, it uses a simple microphone receiver for speech recognition. Simple cameras for face recognition. They put it in shopping malls and the robots didn’t hear anything and couldn’t recognise anything.”

Most competitors do not sell more than 10 robots, hence Kivokurtsev said he would not call them rivals. However, he is certain that the team will see an increasing number of competitors coming to this market, but they will have the same software challenges and Promobot believes it is ahead of the competition by a good margin. “A lot of companies in China are trying to build this, but they don’t understand how to do speech recognition, they don’t understand how to recognise a face.”

And Kivokurtsev and his team are not just waiting for the Chinese to learn. “We will improve our speech recognition system, we will improve our basic face recognition system.”